What exactly are the notes of the violin? Which sounds are produced by this primordial string quartet instrument? These questions may seem blatantly misleading. They are in reality essential to understanding this instrument. Whether you are a beginner violinist or simply curious to learn more on the topic, this article gives a more in-depth look into the notes of the violin.

Notes of the violin

How to distinguish the four strings and four notes of the violin

The open strings

The violin has four strings, each of which can be identified by their diameter and sometimes by the material they’re made of (however, this is not always the case). Friction of the bow against the strings produces vibrations that travel through the taut string and are then transmitted from the bridge to the body of the instrument. The instrument body becomes the resonance chamber, with the sound escaping from the F-holes. Yet how do we explain the difference in sounds produced by the different strings?

Difference in pitch and tone quality has to do with the length, diameter and tension of each string. When you look at a violin that is in playing position—balanced against the clavicle and the jawline—you will be able to notice that the strings gradually become thinner from left to right. The strings are organized in the following order:

On the far left is the open G string, which is the lowest note. Next, we have the open D string, then the open A, and finally the open E. The open E is also called the chanterelle, as it is the thinnest and most high-pitched of the four strings. These notes are achieved by tightening or loosening the strings. And it is in manipulating the pegs and adjusters at the tailpiece that you can change the notes of the violin’s open strings, aka tuning.

Each note has a specific frequency. The higher the frequency, the higher the note will be. With this in mind, here below are the notes of the violin’s open strings (from lowest to highest) with their frequencies:

[pullquote align=”center”]

G = 196Hz

D = 294Hz

A = 440Hz

E = 660Hz

[/pullquote]

[blog_posts orderby=”date” ids=”3467″]

Is the tuning of a violin always the same?

As we have discovered, the most classical way to tune the violin is in fifths. This will be the necessary tuning for most repertoire. However, it is also possible to tune a violin differently in order to simplify certain fingerings. Modification of the classical tuning of the open violin strings is called scordatura and is normally included at the beginning of music scores. You can of course experiment with open-string tuning by coming up with your own chord arrangements, especially for contemporary music.

However, avoid over-tuning your violin, as you will risk snapping the strings. Violin strings are designed to remain at a specific tension and may not take well to constant changes. It is also important to realize that the instrument itself is affected by these various adjustments, which can fundamentally impact the overall tone quality.

G, D, A, E…but what about the other notes?

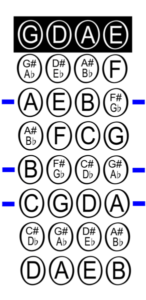

It is from these “open” strings that we can produce all the other notes of the musical scale. Pressing your finger against the string automatically reduces its length. Higher notes are obtained through pression of the strings. For example: from the G string we can play a D (which is also the next open string) by pressing the fourth finger in the first position (see chart below).

A note that is played on a string other than the open will sound slightly different. This allows the violinist to play with the different fingerings depending on the piece, the desired effects and the scales and fingering combinations the piece entails. The numerous fingering possibilities adds to the richness of violin studies (and of bowed string instruments in general).

The violin’s notes and intervals: the perfect fifth

Each note has an interval relationship to the notes that are played before and after it. Here, we are referring to the difference between each note’s pitch. In Western music, these intervals are defined according to tones and semitones. Two notes that appear on the scale next to each other (C and D, for example) are separated by two semitones, otherwise referred to as a major second. E and F as well as B and C are only separated by a semitone, or a half step.

The violin is tuned in fifths, which means that each note is separated from the next by three and a half tones (or seven half steps). This is referred to as a perfect fifth (without alteration).

Do re mi fa sol la si do: the origin of French musical notation

Musical notes attributed to Latin chants

In the eleventh century, a monk named Guido of Arezzo came up with a musical notation system drawing upon the first syllables of an ancient Latin chant. This was done to give each neume (succession of notes sung on one syllable) its own name. This system is considered hexacordal as it is a set of six joint scale degrees with a semi-tone in the middle.

The beginning of each of the six opening lines of the song in question, called the Hymn of Saint John the Baptist, allow us to retrace a whole scale range. Arezzo, using a system called solmization, named each of the notes (in ascending order) ut (C), re (D), mi (E), fa (F), sol (G), la (A).

It was likely Anselm of Flanders who, in the 16th century, created the “B” from the first six lines of Hymn of Saint John the Baptist (here below):

[pullquote align=”center”]

Utqueant laxis

Resonare fibris

Mira gestorum

Famuli tuorum

Solve polluti

Labii reatum

Sancte Iohannes

[/pullquote]

Moving towards a tonal system

From the 16th century onwards, Guido d’Arezzo’s theory of hexacords was not sufficient enough to accompany the musical complexity of the Renaissance, which called for new systems of notation. Indeed, this is when the tonal system slowly began to develop.

Composers such as Loys Bourgeois would define the ut (C) as the beginning of the musical scale. This indeed appears in his 1550 The Direct Road to Music. Then it was Giovanni Maria Bononcini who, in 1640, replaced the term ut with do, which is easier to sing. However, according to other sources, the do actually came from “Dominus” (meaning “lord” in Latin) and would have already appeared in more ancient texts.

The final naming of the notes

The development of the octave-based musical notation system (so do(C), re(D), mi(E), fa(F), sol(G), la(A), si(B), do(C)) was rectified on numerous occasions. These constant changes to the names of notes and variations in syllables underscores the challenge of being able to fully grasp the notion of tonality.

Music conservatories would take over on music education under Napoleon Bonaparte at the end of the 18th century. The religious institutions formerly responsible for teaching music would at this time settle on a final transposition method that is still used today.

English notation: another way to name the violin’s notes

In all likelihood, you have already seen letters instead of Do or Ré. It is in fact a simple difference in notation used in English-speaking countries and inspired by the Antiquity period. Originally, it was fifth century thinker Boethius who, in his De institutione musica (The Principles of Music), names the notes spanning two octaves from A to P. During the Middle Ages, it became the preferred method to maintain just one octave spanning from A to G.

Here is how the two systems translate:

[pullquote align=”center”]

A = La

B = Si

C = Do

D = Ré

E = Mi

F = Fa

G = Sol

[/pullquote]

Here is a tip for memorizing solfège: F for Fa is simple. From there, it is easy to deduce the remaining notes in order, forward or backward. But it is also easy to hear the similarity between La and A and consequently, the order of the notes that follow.

Note that in German-speaking countries, the B is replaced by an H to designate the Si.

What about the notes of the viola and cello?

The viola and cello are always tuned in fifths, but on different pitches: C, G, D, and A. Differences between the two instruments lies not only in their range but also in the way they are played. Generally speaking, the notes of the cello are an octave below those of the viola. Here are their frequencies:

Viola – C = 131Hz G = 196Hz D = 294Hz A = 440Hz

Cello – C = 65Hz G = 98Hz D = 147Hz A = 220Hz

The five-string violin: combining the notes of the violin and viola

The five-string violin, known as the quinton, is a hybrid instrument whose origins date back to the Baroque period. It is a mixture of violin, viola and viola da gamba. Quintons have five strings that combine the C of the viola with the G, D, A and E strings of the violin. Thus, it is possible to obtain the same range of two instruments combined.

It is also possible to acquire a quinton (combining characteristics of violin and viola) from our store.